Getting from point A to point B is sometimes messy even when we are simply walking — wondering if the path is right, if we are going in the right direction, what if we took that shortcut and so on.

But when point A is a user problem and point B is an implemented feature, it’s like navigating in open sea with an old map and a faulty compass.

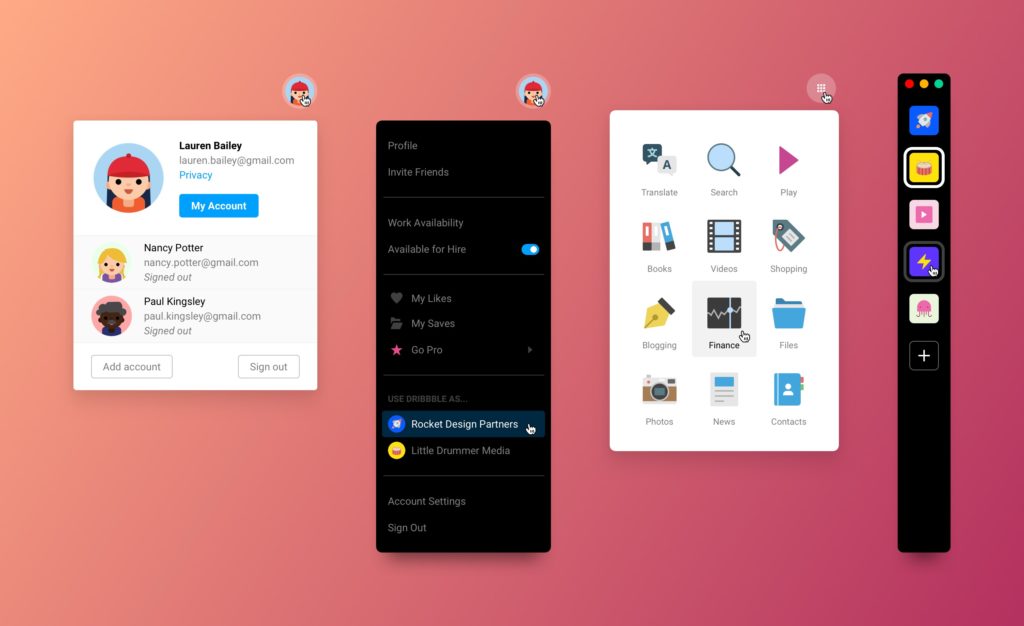

The whole of the process in all its Freudian glory (all illustrations by me)

That is why following a rigorous process — even when time is tight — is key to getting to that point B with as much confidence and data about the solution as possible and — additionally — to make it a little easier the following times (and to build an exhaustive documentation for future generations to come).

1. Understand the problem

Problems need understanding too

First off, how did this request come to life? Was it a customer request, the CEO’s idea, a roadmap step towards the achievement of The Vision? Understanding where that issue on Jira or email or post it with the request came from is pivotal. Discerning the actual problem that triggered the request from the messenger’s added interpretation is often hard and also easy to overlook (and let’s face it, less time consuming).

Traveling back to that initial spark that triggered it means making sure the starting point of the design is the actual problem, and not one of the possible solutions.

Gather insights from customer care, from the CEO, from the Head of Product, whoever and — kind of like a Sigmund Freud of Product Design — dig into that until you hit the source, the original event that sparked the request.

2. Research the problem and gather data

Probing that problem is part of the solution

Step two means getting really good at bothering people and googling things. Once identified that event (might be a childhood trauma or a customer complaint) it’s now time to get as much information as possible on it.

How are other people handling that issue? Is it a widespread problem or a niche issue? Is there a way we can split that problem into smaller problems? And, most importantly, gather data on it.

Even if we are talking about a completely new feature and/or the product is still to be developed, there are metrics that relate to it (to some extent) that can be used. If it’s an improvement of an existing feature it should be easier getting use data from analytics or any kind of metrics that should have been implemented.

3. Re-frame the problem

Blue steel ™

With all that information by now, it should be easy to get a better picture of the problem and the context is exists in. Reframing the problem means getting a different set of eyes and looking at it from another perspective (see J.W. Getzels works on the “Problem of the Problem” and creative problem solving), thus spoiling it from any previous bias or interpretation that might have been added while collecting it.

So, while the original request might have been “we need a feature that allows to transfer money to the user when the balance is low” (which is a request that already contains the solution), the problem that originated it might have been “transferring money to the user is time consuming and requires constantly checking the balance”.

This new framing of the problem opens up new paths towards the solution (either implement a scheduler, or an automatic alert when the balance is low).

4. Design the solution

The Vitruvian Solution

The problem is now identified and data is available to put it into the wider context of the product. It is now time to frame the solution as in “decide which one of these paths is leading to the solution better fit for the problem”.

For this purpose it can be useful to put in the form of questions which features should the solution have — “should the user be able to set an automatic reminder?” “Should the user be able to import events?” — and build a list of possible solution approaches. The aim is to narrow down the options and form an assumption that will be tested with a prototype.

Since the aim is testing the assumption, the prototype would ideally be assumption-centered, ideally stripped from all the frills and unnecessary details that might distract the user when testing.

At this step it is also ideal to chat with the developers and anyone else that will be involved in the process (QA, wider design team, customer care) to gather their insights on the solution from their perspective.

5. Test the solution

“I wonder why they are making me take a math test”

Depending on the resources and time available, user testing is always both challenging and necessary.

Even if the resources are low and time is tight, testing a sample of users that is representative of the larger user base of the product is extremely important, even more so than having a large sample which is not representative and thus, biased (see the Literary Digest case in 1936).

Collecting notes — or better yet record the audio — in the most exhaustive way means it is easier if the interviews are conducted with the help of a UX researcher (if possible, or at least another human being who can write) in order to keep both the quality of the notes and the interview high.