Motion helps make UIs expressive and easy to use. Despite having so much potential, motion is perhaps the least understood of all the design disciplines. This may be due to it being one of the newer members of the UI design family. Visual and interaction design dates back to early GUIs, but motion had to wait for modern hardware to render animation smoothly. The overlap between UI motion and traditional animation also muddies the waters. A lifetime can be spent mastering Disney’s 12 basic principles, does this mean UI motion is similarly complex? People often tell me that designing motion is complicated, or that choosing the right values is ambiguous. I contend that in areas most important to a UI, motion design can and should be simple.

Where to start

Motion’s primary job is to help users navigate an app by illustrating the relationship between UI elements. Motion also has the ability to add character to an app with animated icons, logos, and illustrations; however, establishing usability should take priority over adding expressivity. Before flexing your character animation skills, let’s start with designing a strong motion foundation by focusing on navigation transitions.

Transition patterns

When designing a nav transition, simplicity and consistency are key. To achieve this, we’ll choose from two types of motion patterns:

- Transitions based on a container

- Transitions without a container.

Transitions based on a container

If a composition involves a container like a button, card or list, then the transition design is based on animating the container. Containers are usually easy to spot based on their visible edges, but remember they can also be invisible until the transition starts, like a list item with no dividers. This pattern breaks down into three steps:

1. Animate the container using Material’s standard easing (meaning it speeds up quickly and then gently slows to rest). In this example, the container’s dimensions and corner radii animate from a circular button to a rectangle that fills the screen.

2. Scale elements in the container to fit to width. Elements are pinned to the top and masked inside the container. This creates a clear connection between the container and the elements inside.

3. Elements that exit during the transition fade out as the container accelerates. Elements that enter fade in as the container decelerates. A seamless sleight of hand effect is achieved by fading elements as they move quickly.

Applying this pattern to all transitions involving a container establishes a consistent style. It also makes the relationship between the start and end compositions clear since they’re linked by the animated container. To show the flexibility of this pattern, here it is applied to five different compositions:

Some containers simply slide in from off screen using Material’s standard easing. The direction it slides from is informed by the location of the component it’s associated with. For example, tapping a nav drawer icon in the top left will slide the container in from the left.

If a container enters from within the screen bounds, it fades in and scales up. Instead of animating from 0% scale, it starts at 95% to avoid drawing excessive attention to the transition. The scale animation uses Material’s deceleration easing, meaning it starts at peak velocity and gently slows to rest. To exit, the container simply fades out without scaling. Exit animations are designed to be subtler than entrances to focus attention on new content.

Transitions without a container

Some compositions will not have a container to base the transition design on, like tapping an icon in a bottom nav that brings the user to a new destination. In these cases, a two-step pattern is used:

- The start composition exits by fading out, then the end composition enters by fading in.

- As the end composition fades in, it also subtly scales up using Material’s deceleration easing. Again, scale is only applied to the entering composition to emphasize new content over old.

If the start and end compositions have a clear spatial or sequential relationship, shared motion can be used to reinforce it. When navigating a stepper component for example, the start and end compositions share a vertical sliding motion as they fade. This reinforces their vertical layout. When tapping the next button in an onboarding flow, the compositions share a horizontal sliding motion. Moving left to right reinforces the notion of progressing in a sequence. Shared motion uses Material’s standard easing.

Best practices

Keep it simple

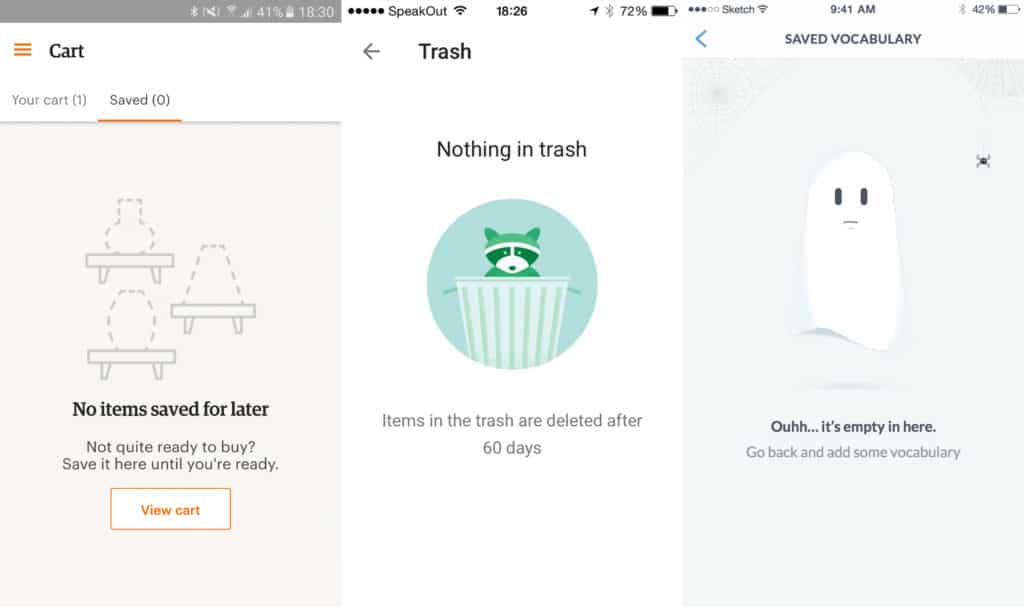

Given their high frequency and close ties to usability, nav transitions should generally favor functionality over style. This isn’t to say they should never be stylized, just be sure style choices are justified by the brand. Eye catching motion is usually best reserved for elements like small icons, logos, loaders, or empty states. The simple example below might not get as much attention on Dribbble, but it will make for a more usable app.

Choose the right duration and easing

Nav transitions should use durations that prioritize functionality by being quick, but not so fast that they become disorienting. Durations are chosen based on how much of the screen the animation occupies. Since nav transitions usually occupy most of the screen, a long duration of 300ms is a good rule of thumb. In contrast, small components like a switch use a short duration of 100ms. If a transition feels too fast or slow, adjust its duration in 25ms increments until it strikes the right balance.

Easing describes the rate that animations speed up and slow down. Most nav transitions use Material’s standard easing, which is an asymmetrical easing type. This means elements quickly speed up and then gently slow down to focus attention on the end of the transition. This type of easing gives animations a natural quality, since objects in the real world don’t instantly start or stop moving. If a transition appears stiff or robotic, it’s likely symmetrical or linear easing has been mistakenly chosen.