BY Arturo Ríos

That was the first time almost a year ago that I did a whiteboard challenge for a UX job interview, which was reviewed by a team of experienced designers. Since it was a remote session, I had to find a quiet space for the exercise, buy a bigger whiteboard and prepare to spend 40 minutes solving a challenge.

I had no idea how to approach the exercise; it was going to be 100% improvisation, no way to plan ahead, or anticipate the problem I would solve.

At the end everything worked out. I learned a lot, landed the job, and more importantly, I became an advocate of facilitating whiteboard sessions.

As of now, there is no day at work that I do not leverage a whiteboard, either by myself or with my team, to discuss the problems that arise on our projects and to explore a wide range of solutions, hence increasing the confidence and alignment of my peers over the goal we’re pursuing and the challenge we’re solving together.

The importance of Whiteboard Exercises

Maybe you’re an in-house designer who regularly works with product managers, project managers, developers, marketing strategists and business teams, and you’re interested in fostering more collaborative sessions, in order to give your team a safe space to propose new ideas.

Perhaps you’re a UX practitioner looking for new challenges in your career by applying for a new role, and you know that eventually you might be presented with a whiteboard challenge (or even four, if you’re applying to Google) in order for hiring managers to review your design process and your decision-making.

Whether whiteboard challenges for hiring purposes are optimal or not, they’re one of the most cost-effective exercises you can run with your team to reduce uncertainty in the development of your projects, as they are effortless in terms of additional resources to have, quick to iterate, and collaborative by nature.

Christian Silva, UX Lead at Wizeline, shares his story about how the initial design team at Wizeline would sometimes spend entire days whiteboarding together to build shared understanding ofthe challenges they were facing at the time:

We would spend two straight days doing whiteboarding exercises before committing to build anything, because we knew that we were early in the process and having the team aligned with what we were pursuing at the beginning was key to scale our product in the right direction.

He approaches whiteboard sessions as not only a way to discuss issues but as a tool that allows other team members — such as developers — to raise their own ideas and give them confidence to participate in the design process, so the solutions the team agree on are grounded based on different perspectives.

Through whiteboard exercises, you can give your team a channel and voice to propose new ideas, a shared language.

While facilitating whiteboard sessions might seem fairly easy to do, they are hard to master off the bat, as they can easily get out of hand if the facilitator is not prepared to guide the team and conversations through the most crucial topics.

The following are some recommendations to consider while facilitating these exercises with your team or during a whiteboard challenge for a UX position, as they are based on the experience of Senior Designers from well-known Startups who have conducted and reviewed hundreds of them, as well as my own learnings (and mistakes) while exercising UX on a wide range of projects.

Always Start at the End

The most unproductive exercise is the one in which all the participants are trying to solve different problems. In order to avoid this scenario, it is important to set the expectations of the exercise prior to gathering your team for the session. This might sound like a no-brainer, but by including the objectives in the calendar invite or through your communication channels, you allow team members to be on the same page before running the session, and thus mitigating the risk of them feeling that their participation is not contributing to the project (check the whiteboard canvas template below for more context around this insight).

Problem Space vs Solution Space

If the first thing you do while taking over whiteboard exercises is drawing boxes and arrows and ideate around solutions, maybe you’re doing something wrong. If you focus only on the solution space, chances are you might miss crucial information belonging to the problem space such as user goals & pain points, context of use, assumptions the team is making, risks the project might face — to name a few. Instead, take the time to bring these conversations with the rest of the team and ask them a lot of questions to fully understand the challenge you’re trying to solve.

Ideally you should spend at least half of the exercise exploring the problem space and constraints around the goal, and the other half ideating around potential solutions to deep dive on.

Run away from the details

Putting too much emphasis on the nitty-gritty of a solution can diminish the overall quantity and quality of your ideas, given that you might stop seeing the forest from the trees when entering in tunnel vision with a specific problem or solution.

Instead of trying to draw the straightest line in the world or crafting the most dribbble-worthy user flow, start with high-level concepts or not-so polished vague ideas you would like to further explore, once the team reviews all the possibilities at hand. Florian Lissot, Senior UX Designer at Wizeline, knows the power of building on top of ideas from other participants, and reaching better solutions that combine the previous experiences of the team:

The concepts discussed during whiteboard sessions should not be as if they were written in stone, but rather as doors that can open new ideas for the team to explore.

In his book User Story Mapping, Jeff Patton gives invaluable advice about “thinking mile wide, inch deep” when running User Story Mapping sessions, an exercise used by agile teams to break down development efforts into stories. He elaborates that when trying to bring shared understanding to the team as to what they should build, it is better to get to the end of the story before getting lost in the details.

Focus on the breadth of the story before diving into the deep.

This advice can be totally applicable to whiteboard exercises. Instead of stopping at the middle of a possible user flow and trying to come up with all the possible edge cases, it is better to draw the big picture of the solution you’re trying to achieve, discuss its feasibility, and then move on with the exercise. The most important aspect of whiteboard sessions should not be coming up with the best solution, but having the right conversations early in the process.

Divide and Conquer [freebie included]

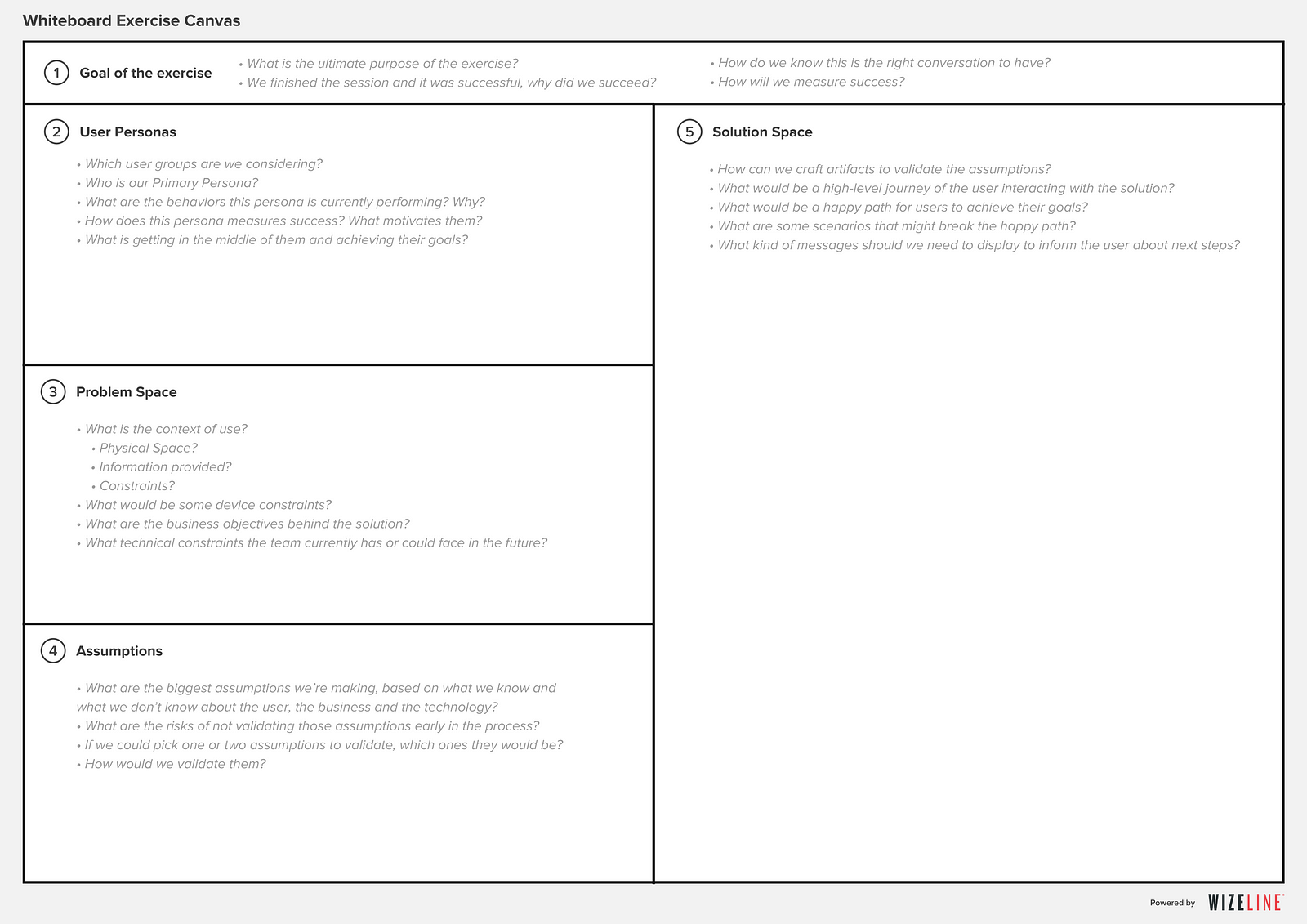

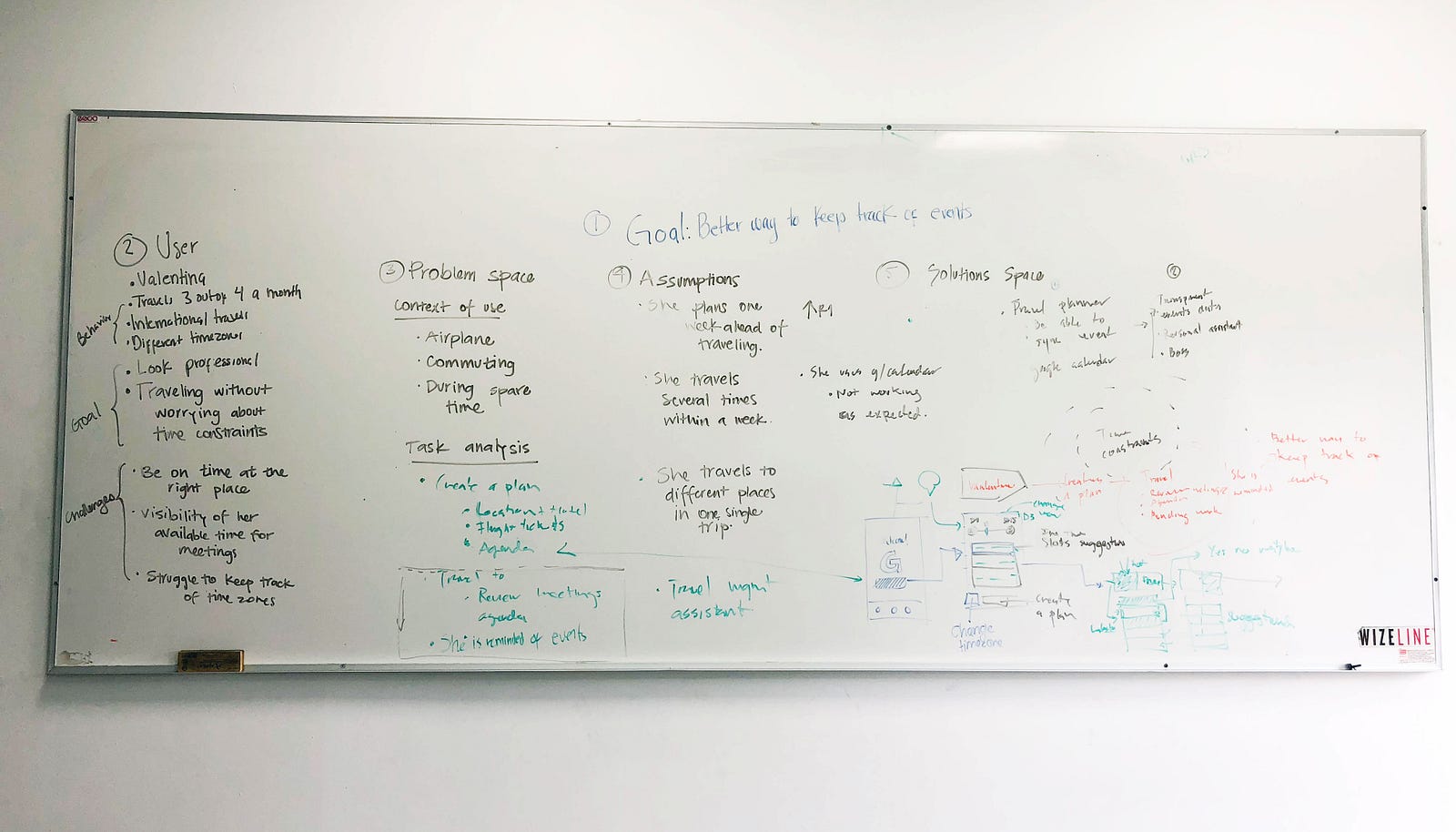

Chances are that during your whiteboard exercises you will be constrained by time and space, so planning every one of your movements and decisions will be key to set you out for a successful session. You can use the following structure I have put together as a baseline to run your whiteboard exercises smoothly.

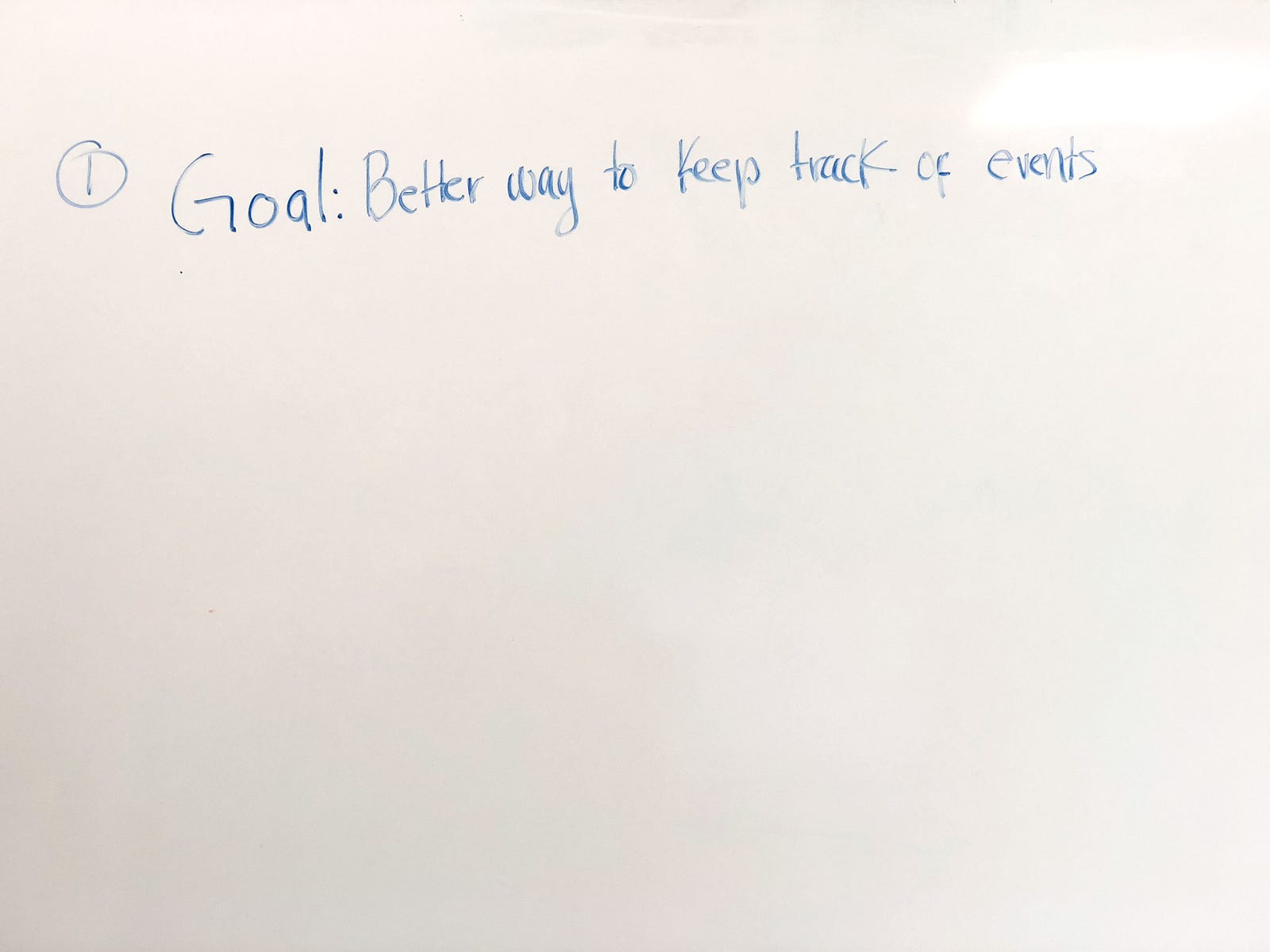

1. The Goal

At the very top of the whiteboard you should write down the ultimate goal of the session, the objective you’re trying to achieve (if you’re into OKRs, you might even want to add a way to measure the goal) so it is always visible for your team.

As Jake Knapp states in his stellar book Design Sprint, people’s short-term memory is not all that great, but our spatial memory is awesome (hence the effectiveness of techniques such as memory palace); by always having visible goals of what you want to achieve, you’re reducing the possibilities of the session to go off the rails and fall into unproductive discussions.

Conversations to have during this step:

- What is the ultimate purpose of doing this exercise?

- Let’s say we had an outstanding session, what did we accomplish? Why did it work?

- How can we know that such objective is the right one to pursue?

- How will we know if this is true?

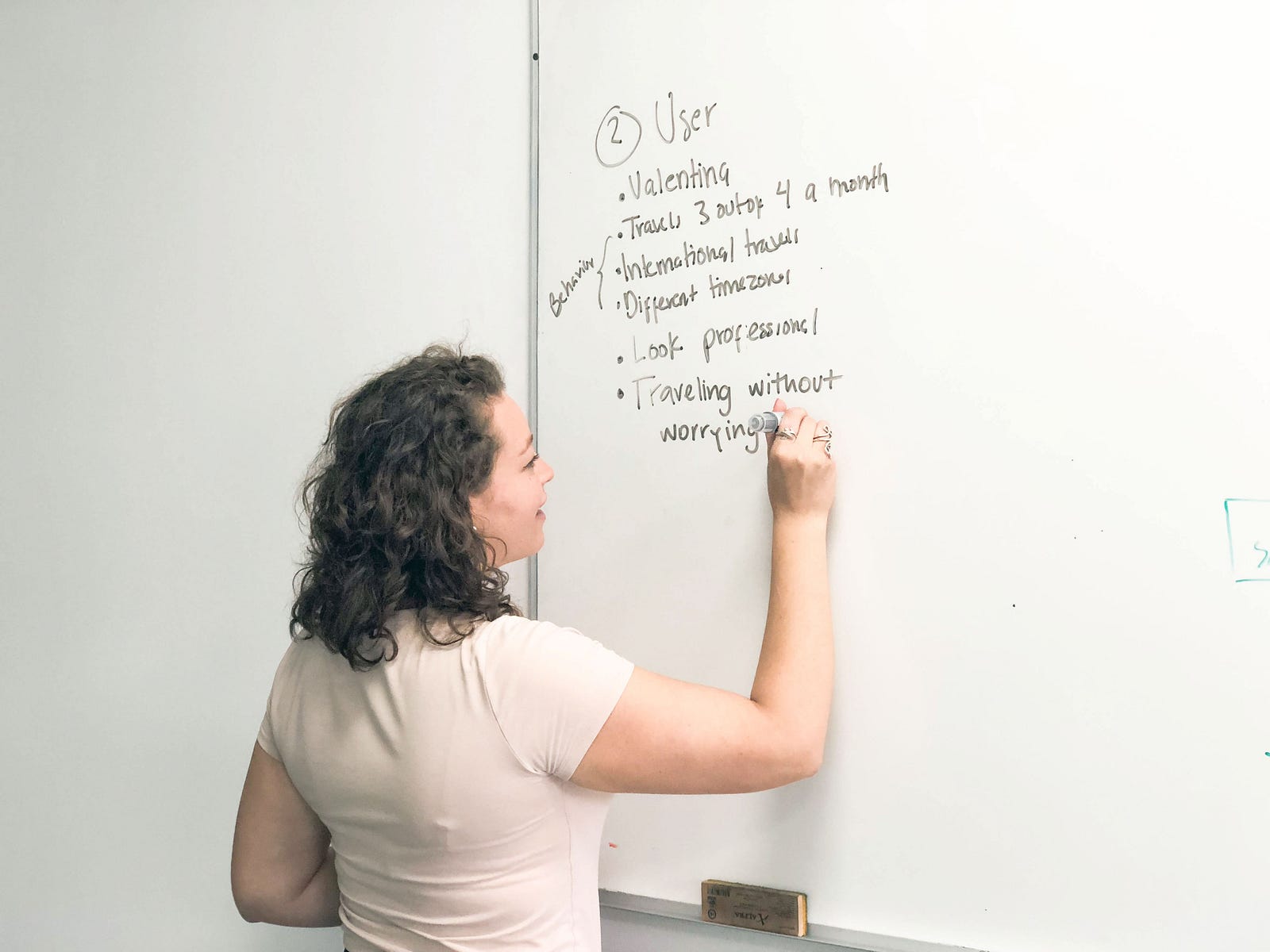

2. The User

At some point we should pay respect to the UX title we have on our business cards, and after agreeing on the goal, the best next step is to bring the user into the conversation. Ask the participants what assumptions are being made around the target users; how many user groups are being considered; which is the primary group; decide the persona you will be focusing on (it might not be the primary one all the time) and depending on the input you receive, you can do a quick list of behaviors, goals, motivations, frustrations and challenges you might know (or not know, which should be properly differentiated) about the the User Persona. You can even deploy a full Proto-Persona brain dump if necessary (see this post about approaching a Persona through 4 quadrants).

Conversations to have during this step:

- What are our User Groups?

- Who is the Primary Persona?

- What are some current behaviors they’re performing?

- What motivates them?

- How do they measure success?

- What is getting in the middle of them and achieving their goals?

3. The Problem Space

While advocating for the user might be one of our top priorities, it is only a third of the problem. Within the problem space, you should explore the the context in which the behaviors are performed, the business goals the organization is trying to accomplish while building the product, as well as the technical constraints the development team might face during the implementation of the solution.

Conversations to have during this step:

- What is the context of use? Where do the behaviors happen?

- What informations does the user have at hand?

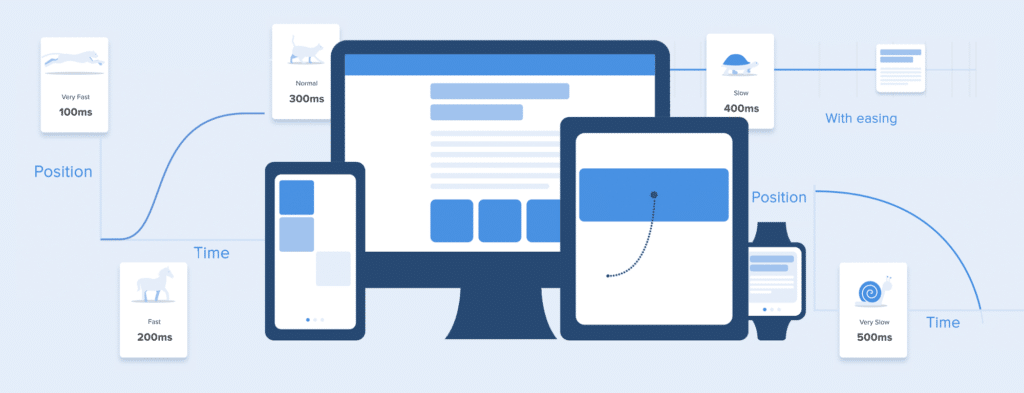

- What would be some device/artifact constraints?

- What are the business objectives behind the solution?

- What technical constraints the team currently has or could face in the future?

4. Assumptions

By considering the main goal, user groups, business goals and technical constraints, the team should have found insights that might feel risky not to validate. These insights can be written in the assumptions section, in order for participants to make a differentiation between what they know for a fact and what they should research prior making important decisions.

5. Solution Space

If you’ve considered the previous steps before starting proposing solutions, you will feel more confident about the solutions you start sketching on the whiteboard.

Start with a high-level journey of the user accomplishing the main goal (sometimes known as happy path), and discuss the minimum steps it might take to reach such milestone. If you feel confident enough with the scenario followed, you can start exploring interface components, layouts, and interactions that should be part of the solution in order to facilitate the experience of the users.

Make sure that all the participants are engaged during the session. You can use the format “yes, and” to encourage team members to build on top of the ideas of others.

Once you spent some time exploring concepts, you should decide which solution is the most feasible one, and even trying to make it fail. What could possibly go wrong here? What are some edge cases we should be mindful of?Asking what if questions at this point is recommended, as they do not discourage the ideation process, but keep solutions achievable.

By now you should have a whiteboard full of questions, assumptions and ideas to further explore, as well as a team aligned over the design decisions to make.

1 Comment